The desire to make available (from limited) opportunities and resources to deserving people on the basis of merit is a key belief in modern society. Recognising and rewarding merit is often seen as the way to build a fairer, more equitable society. The sentiment is noble and the intent laudable.

Yet there are serious problems with the concept of “merit”.

In this post I will discuss (in my opinion) some common myths about merit and the pitfalls with the “meritocratic system” . Disclaimer: I want to be clear that merit as a concept is important and useful when (and where) it is applicable.

1.Privilge, our self worth and merit: Judging who gets entry to the group that we belong to (be it a company, club, course, society, …) is wrapped up in our own sense of self worth. Implicit in the belief that the system really measures “merit” is the justification for our own presence. Thus, if someone doesnt make the cut they dont have merit. Conversely, if the system was not fairly measuring merit, it could imply our presence was through privilge rather than merit. We shy away from this and take refuge in the comforting belief of merit. Emotionally it can be hard to accept that we are not the most deserving people for that spot inspite of all our efforts, talent and knowledge. This can at times cloud our judgement regarding “merit”. Recognising the privilge we may have is critical to deal with our biases when thinking of merit.

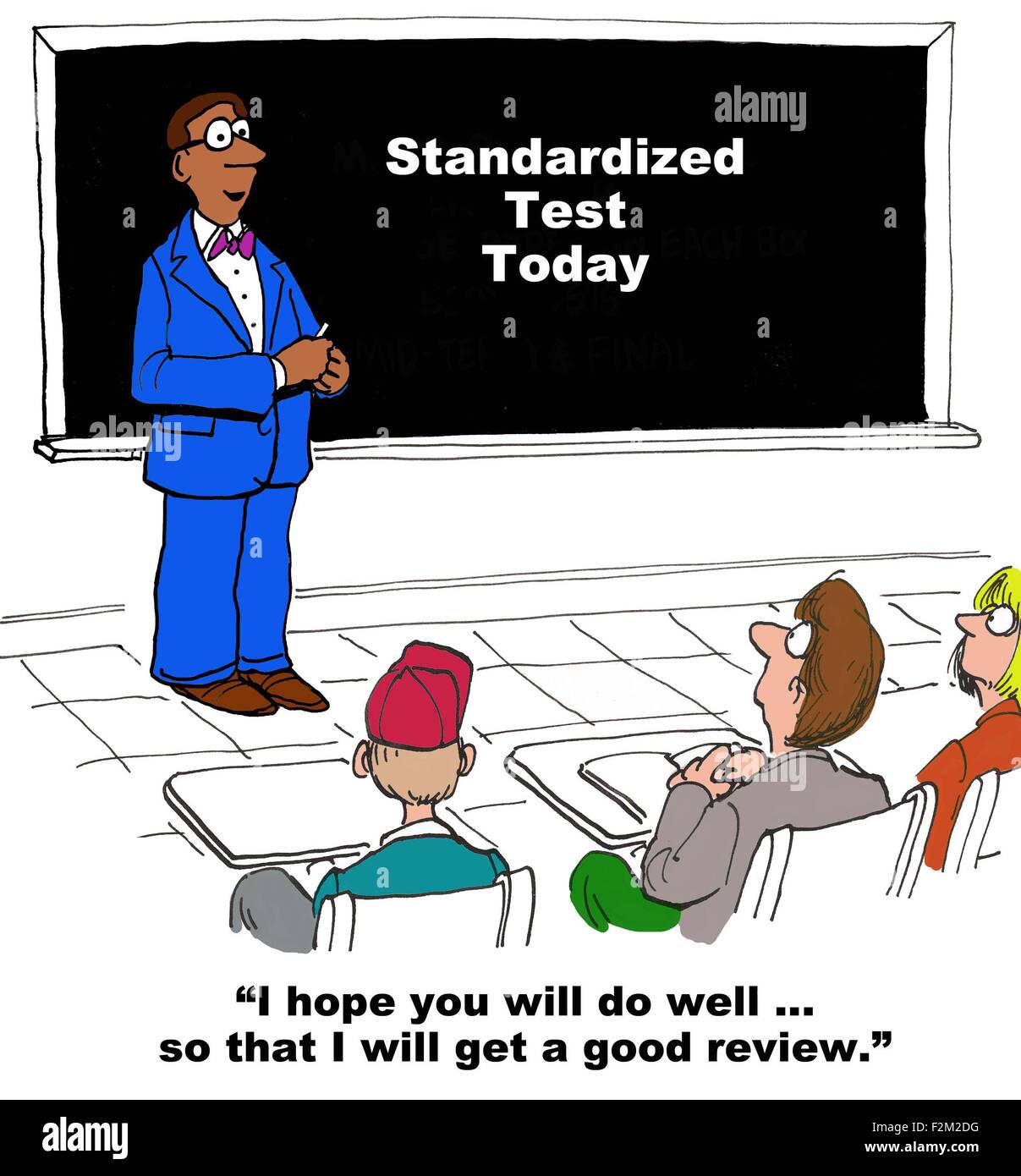

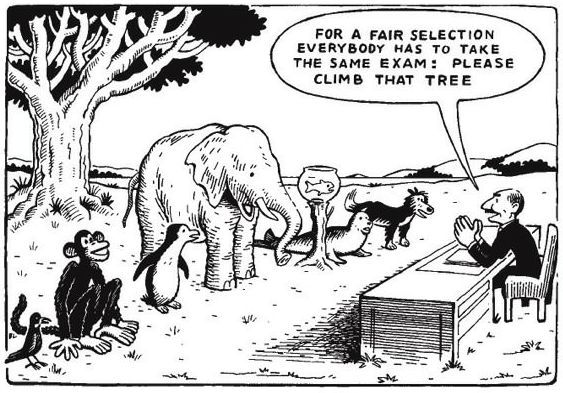

2. Tests allow testing for pure “merit”: We see exams and tests administered to students (for entry to a course), job applicants (for employment), promotion aspirants etc. The underlying belief here is that the same test administered to all applicants, makes it a fair and equal way to judge merit. This is not really correct! The tests can miss completely that:

All applicants do not have similar “test taking” skills, even if they have the required knowledge and experience for the role/course etc. Equality is not equity. For example, some people could explain the answers verbally much better than writing them down. Yet a written exam would disadvantage them. How would someone dyslexic compare with someone who is not? Are we testing for knowledge/skills or for writing ability? Some people may have had great coaching/help with public speaking and interviewing, giving them an advantage over competitors from less privilged upbringing, schools etc.

Our reach may be limited (due to our system limitations on accessibility, biases, lack of engagement from minority groups, practical constraints etc. ) and we may not even be testing the people with most “merit”. Thus our merit test may only be looking at a small pool of the usual suspects, and missing out on well suited people. Effectively, the question is: are we judging merit by testing for the right thing in the right way?

3. Criteria around merit are subjective: the deep rooted faith that objective criteria (fair to all and not discriminatory towards any group) are possible ignores the reality of human beings (with personal biases) setting up the criteria. Criteria to judge and decide merit have to originate somewhere and evolve over time. They are influenced by the limitations of social convention, andlimited or skewed data, by who is involved (who is left out) in the decisions and their personal prejudices. Unfair practices, outmoded ways of thinking sit inside merit criteria and have to be actively weeded out. While the work on DEI, fairness, productivity etc. drive this change, we need to understand that even the benchmarks used to judge merit may well be skewed and at times outrightly unjust, exclusionary.

I want to take an historical example of opportunity to illustrate the point: voting rights for women (in most Western democracies) did not arrive all at once: Suffrage moved from no women voting to only landed women voting to women over a certain age voting to universal suffrage.. with back and forth in between. The right to vote had fairly arbitrary “merit” criteria that changed over time (being rich enough to be a landowner, being over a certain age…) and reflected the then social conventions, the lack of power in the hands of those whose “merit” was being denied and the prejudices of the lawmakers.

Here are a couple of blogposts (meritocracy unveiling the paradox and meritocracy by Getonboard)I enjoyed reading that summarised a good book, and an article pertinent to this topic.

What is your personal experience of recognising your bias in merit?